The search for the worst anthro job ad: An interview with Dada Docot

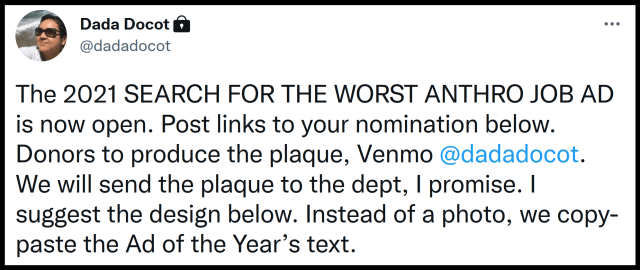

In September 2021, Dada Docot sent out a half-serious tweet about finding the Worse Anthro Job Ad for 2021. The post got attention, and the search took off. The two threads of the search (for gathering nominations and announcement of results) registered about 173,536 impressions as of February 2022. The search received a total of $129 from 24 supporters (4 postdocs, 3 researchers, 4 asst profs, 3 assoc profs, 3 PhD students, 2 VAPs, 2 full profs, and 2 alt-ACs). These donations will be used to buy plaques for the two main winners and the 13 nominees. The winners were announced on 11/21/21 during the 2021 AAA meetings. Dr. Docot is an assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Purdue University and a postdoctoral fellow at Tokyo College, University of Tokyo, currently establishing AH&A non-lab. You can find her on Twitter here.

Ryan Anderson (RA): Thanks so much for doing this interview, Dada. As someone who has dealt with the anthro job market in the recent past, I really appreciated both the humor and the critique of your Worst Anthro Job Ad search. Anyone who has been through the job market in anthropology knows just how bad, inconsistent, and terrible it can be. All the documents, the vague instructions, the deadlines…all that labor, time, and hope that goes into it. And often all that labor (and hope) just goes down a black hole, because for most applications there’s very little if any response. Applicants are just supposed to deal with it, and if things don’t work out try again next year. It’s such an impersonal process, and jobs are so scarce, so there aren’t too many opportunities to call out the process or push back. But this is what you managed to do with this Twitter thread. You helped create a space for some critical push back on how we do this anthro job market thing. What was it that sparked this idea? Was this something you’d been thinking about for a while or did you just post it on a whim? And did you think it would take off the way it did?

Dada Docot: (DD): Thank you, Ryan and Anthrodendum, for the space to do this interview which highlights the 2021 Search for the Worst Anthro Job Ad. I am tremendously grateful for all the support the Search has received — from sponsors who sent donations, people on the job market who sent in nominations, the members of the panel of judges who committed time to the project, and folks on Twitter who helped spread the word. I try to do what I can, even in the most minute way, to cultivate better practices in academia, especially in the field of anthropology. As anthropologists, we write about empathy, generosity, and social justice, and it would be life-changing if we could consciously apply these themes to academic practices. In my twitter thread, I wrote that the project is meant to be a public demand for anthropology departments to do better. At the 2019 American Anthropological Association meetings, I launched a project that I called “BINGO for Anthropologists of Color.” It was a literal BINGO game with printed BINGO cards that conference attendees of color could get from several spots in the conference areas. I am interested in interventions that bring attention to struggles experienced by anthropologists, but I try to do them in creative ways, and sometimes with humor, because critique could also be joyful and playful.

I think many of us are intimately familiar with the pressures of the academic job market. We also remember the research done by Nick Kawa et al which exposes inequalities in American anthropology hiring practices. The authors write that American anthropology departments recruit only from a limited set of elite institutions. Anxieties surrounding the job market intensified even more during the pandemic as many job searches were canceled due to budget cuts everywhere. Through the thread, I also hoped to express solidarity with friends and folks experiencing stress from the job market and who are additionally burdened by the unreasonable documentation required by the hiring departments. I sometimes find myself doom-scrolling on Twitter and in my feed there are commentaries about the ridiculousness of the job ads which seem to have been getting more demanding since 2017 when I was on the job market for the first time. I did not plan the search and my original post was an impulse response to commentaries on Twitter. I decided on the next steps based on people’s response. I did not expect much support. In fact, as an untenured assistant professor, I was mostly worried that folks would respond to it negatively to say that I don’t appear to be taking academia seriously. To my delight, colleagues in academia and beyond responded favorably to the thread. I hope it will have some impact on future job searches.

RA: I was wondering how people would respond too…and it was pretty positive. I was amazed but like you, glad to see it. I think it’s important how your project puts a spotlight on something that just keeps happening, again and again. It’s one of those sort of bureaucratic practices that many people didn’t feel like they could do much about. It feels impossible, so applicants just deal with it. I think a lot about how practices like this can actually change. Like what actually compels people to change what they’re doing. We’ve seen some change, finally, with the whole asking-for-recommendation-letters up front thing. Although of course there are still holdouts. But I think there’s movement there. Right? But what about the rest of the job ad process? What’s the number one thing you’d like to see changed, like tomorrow?

DD: I agree with you that the job application process indeed seems like one of those things that we have no control over. However, there are mechanisms that could make the job application process in anthropology better. The Job Board Policies of the AAA explicitly states: “Solicitation of letters of recommendation should occur only after an initial screening of candidates to minimize inconvenience to applicants and referees. Names of references may be requested, however.” On Twitter, I read that Rine Vieth had actually emailed the AAA to ask why some job postings on the AAA website still require recommendation letters upfront despite their job board policy. The AAA responded that some departments have to follow local university and HR requirements, including asking for recommendation letters. Excluding job posts which do not follow the job board policy would limit the options for potential candidates. I do not have enough exposure yet to know up to what extent departments and the AAA can actually push back and work together to change universities’ policy, but that would require extra work. I also think that departments with a long list of requirements would drive away some potential applicants, so it’s in their interest too to post less exclusionary ads in order to broaden their pool of candidates.

On your question what is the first thing I would like to see changed – I think the nominations received draw a very clear picture of what job applicants would like to not see in the job ads, and myself and my fellow members in the panel of judges would like to support that: job applicants would like application documents reduced in the first round of screening. Joining me as judge and in writing the essay are Ilana Gershon (Professor, Indiana University), Dannah Dennis (Visiting Assistant Professor, Bucknell College), Danielle Gendron (Ph.D. Candidate, University of British Columbia), and Jena Barchas-Lichenstein (Researcher, Knology).

We awarded two joint co-winners in the search. The first is Grinnell College, whose job received three nominations. Grinnell required upfront a long list of documents including a cover letter, CV, transcripts, a diversity statement, and six course descriptions. One of the awardees of a “dishonorable mention” Oberlin College, which required 9 items! Other anthropology departments like in Washington University in St. Louis asked for three writing samples, and for that, the panel of judges awarded them a “dishonorable mention” for contributing to the “Publications Arms Race.” Required multiple writing samples contributes to the audit culture in academia. Recommendation letters are time-consuming for everyone involved, and should come at a later stage. Applicants, faculty on the search committee, and department staff, become overburdened by all these documents that they need to compile, read, and assess. It seems reasonable that reducing the number of required documents will benefit everyone concerned.

The search did not have a special mention for “Best Anthro Job Ad” but in my DMs, a couple of nominating anthropologists referred to the job ad of Ohio State University’s Anthropology Department which had only three requirements in the first round: a cover letter, CV, and names of three recommenders. Shout out to Ohio State Anthropology for giving us a great model that other departments could emulate!

RA: An overall reduction in the number of documents would be a good step forward. When I was actively on the job market a few years back, I was looking at academic and non-academic positions. One thing that was striking in the non-ac job market was how much less paperwork was required. Just less stuff. You filled out your application, maybe sent in a short cover letter, and that was it. Compared to the huge pile of required documents that many academic jobs ask for, it was kind of amazing. But the bigger point–as you mention–is that this all amounts to people’s time and labor. It’s a ton of work–for applicants and for the people who write their letters. So I think a lot of people would be happy to see a shift toward jobs that require cover letters, CVs, and names of references become the norm. That would help. Is there anything else you’d want to see changed? What about adding more clarity to the process? Like telling people what, exactly, the search committee is hoping for when they ask for x, y, or z document? How long? What do you want to know? Some of the prompts for these documents are just so incredibly opaque!

DD: I completely agree with you that anthropology departments should consider providing more detailed information in their job ads. Don’t we often get frustrated reading “open rank” or “open search” job ads, and isn’t it so mysterious when departments advertise an open rank search? I think it would be helpful if departments could state openly what exactly they are looking for, and what other forms of support they can offer so that the job application process isn’t like a guessing game. For example, we don’t commonly see jobs ads stating salary range, relocation benefits, visa support, etc. Not all applicants have the time and resources to apply for vaguely worded openings, so the pool might not actually be diversifying as much as departments would want. I think many of us, especially first-generation PhDs and those from marginalized communities may not have the network needed to be able to negotiate the best salary. I feel that the job application process could be improved significantly by rethinking it within the space of empathy and transparency. Job ads signal the hiring committee’s respect (or dearth thereof) for the time and energy of the applicants in a very tight and uncertain labor market. They also reflect departmental efforts in establishing better practices. Demystifying the job ad and the selection process (but this is another story) would be a good start for anthropology departments committed to inclusivity.

RA: That would definitely be a good start. Hopefully more departments and search committees start rethinking this stuff. Let’s see some changes here folks. Salary is a clear example of the problem. As you say above, job ads should just go ahead and clearly state the salary range…but they generally do not. It’s so rare when you see a salary range listed for a position in anthropology. So first of all applicants often have little information about the pay of the position they are applying for, and when it comes time for negotiation they have a pretty severe disadvantage. This is the kind of problem that just keeps paving the way for entrenched pay inequities, and transparency could help a lot. Taking the relatively simple step of listing a salary range could be a step forward. But I want to go back to the issue of recommendation letters, especially in light of what is happening with Harvard right now. One of the problems, which you talked about above, is just the sheer amount of labor that results from requiring letters up front. But recommendation letters can also be problematic because of how they intersect with and perpetuate power dynamics within anthropology (and academia more broadly). Letters can all too easily reinforce those power dynamics and hierarchies, and it gets worse when we account for the kinds of abuse and harassment that we’re hearing about with the Harvard case. I had never really thought about this before, but your idea was to just ditch those letters altogether?

DD: On February 10, amidst conversations on social media about the events at Harvard, I said on Twitter if recommendation letters intensify fear and perpetuate inequality among institutions, fueling a cycle of abuse of power, and if scholars can write about their work powerfully in their dossiers, is it about time that job searches stop requiring recommendation letters? I then added a poll, and although totally unofficial, it received 177 votes, 88.1% of which were in favor of abolishing the recommendation letter. Fellow anthropologists responded to my question with various testimonials about recommendation letters as unnecessarily overburdening everyone involved; useful documents that may powerfully articulate the candidate’s fit; sometimes weaponized by advisors to discipline students, etc.

Recommendation letters work as a character check if the applicant is a good co-worker, collegial, and professional. I think that expectations of “fit” in terms of character and professionalism may be unfruitful to those working hard against the neoliberalization of the academy. Those who do not fit may be perceived as “troublemakers” who express their opinion, launch signature campaigns, and do the difficult work of dismantling structures of oppression in the white settler academy. I think the question of whether recommendation letters should stay or not go well beyond our aspirations to have less workload. Many of us enjoy writing letters as a form of paying it forward and continuing to nurture relationships among advisees, mentees, and peers. However, within the academy, where power is uneven, recommendation letters can hurt applicants, especially women and folks from marginalized communities. We now know from the Harvard context, but also from the stories of our friends and peers, that recommendation letters can potentially make or break careers. These letters end up reinforcing a system that is potentially disastrous to those who have less access to power and elite networks.

I think we have to continue reimagining academia and how it can become more generous, empathetic, and supportive. I would also like to note that my fellow judges in the search and myself have a forthcoming collaborative essay about the search (Jena chose to abstain from participating from the essay because of her affiliation with the journal we are submitting the piece to). In our conclusion, we write several recommendations for anthropology job searches. Coming from different positionalities and career stages, we did not reach a consensus on recommending that departments should remove recommendation letters altogether in their future search. However, I lean towards retiring recommendation letters eventually. If applicants cannot demonstrate the fullness of their work and character in their dossier, that means departments could train graduate students how to assemble an effective application packet. There are options such as having a dedicated portion during interviews for learning about applicants’ engagement, work ethic, and other information that the committee would usually look for in recommendation letters. We need to see more search committees experimenting with a job search process geared towards inclusion, which shifts power away from influential institutions and a select few.

RA: That’s a powerful note to end on. Thank you again for taking the time to do this interview, Dada.

DD: Thanks for your time and for having me here. Thanks for helping cast a spotlight on the anthropology job search process. Mabalos at ingat (thank you and take care)!

Ryan Anderson is a cultural and environmental anthropologist.

One Reply to “The search for the worst anthro job ad: An interview with Dada Docot”

One problem is that departments might not be in control of the format and requirements of job submissions. Our HR was recently re-populated by HR professionals who have these quite rigid and extensive bureaucratic requirements. Certainly drove us faculty nuts, we didn’t want to go through 100s of pages of letters, papers, transcripts, for each and every applicant! Not only did we have to require this much information, we then had to fill in excel sheets validating every single time we said – “hey, this person doesn’t teach or do ANYTHING we need, so not moving to the next tier.”