Roam If You Want To

You already know how to use Roam Research, the new note taking app taking the internet by storm. You don’t need to follow the #roamcult hashtag on Twitter, or watch the dozens of YouTube explainer videos in order to start using Roam. If you’ve used Wikipedia (with its web of interlinked definitions), an outliner (with information organized by indented bullet points), Twitter (where you can find subjects by #hashtags), or any desktop computer (where items can exist in multiple locations via the use of an alias or shortcut), then you are already familiar with the main building blocks of Roam. What makes Roam “new” isn’t these tools, but how they have been put together. In short, Roam is much more than the sum of its parts.

Before I go any further, I need to issue a few caveats. The day I posted this, Roam temporarily stopped taking new users. Then the next day they announced that they will start charging, and it won’t be cheap. And even if the waitlist and fee doesn’t put you off, it is important to remember that Roam is still a beta app, so don’t want to trust your life’s work to it.1 But this post isn’t meant to be a how-to,2 or a review, or even an encouragement to use Roam. Instead I want to talk about what makes Roam special. I think Roam offers a new paradigm for how we take notes, one that other apps will surely strive to copy.

So what is it like to use Roam? At its heart Roam is basically an outliner. When you open a new blank document you are presented with a bullet point. You can add new bullets below it, or nest them inside each other, just like any other outliner. If you’ve used Workflowy or Dynalist Roam will feel vary familiar.

Like those apps you can also add tags to each item. This means that it can do many of the same tricks I wrote about in my post from two years ago about how to Roll Your Own QDA (Qualitative Data Analysis) software. Roam lacks some of the niceties of these more polished outlining apps, but it more makes up for that with its own special sauce: “Linked References.”

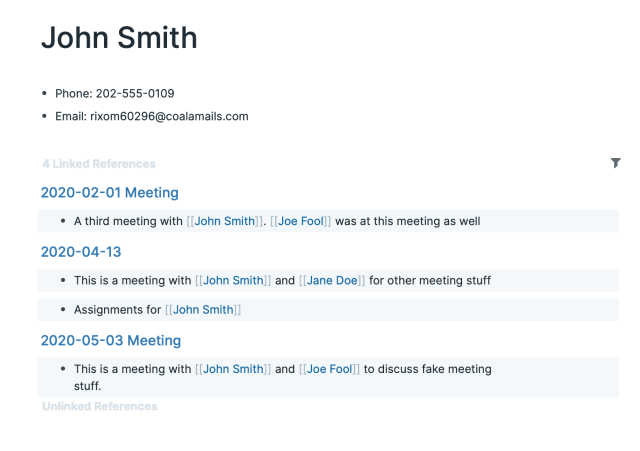

Linked References appears as a section at the bottom of every page and shows you a list of all the documents that link back to the current page. This is the main magic which makes Roam so revolutionary. Imagine you have a note for a contact named “John Smith” and you also have half a dozen notes about meetings where John Smith was present. If you remembered to link his name each time you typed it (Roam makes it easy to turn anything you’ve typed into links), all those meeting notes will appear as a neat little list in your Linked References section. And even if you forgot to turn John Smith’s name into links, Roam will still catch it in a section called, unsurprisingly, “Unlinked References.” (And there is an option to turn those into real links if you like.)

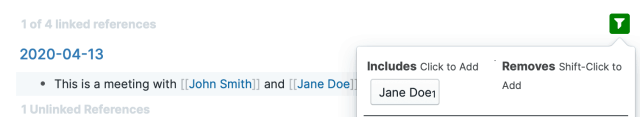

A lot of apps allow you to add tags to notes as you write. (One of my favorites is called Bear.) In any of these apps, if you click on a tag you will see a list of all the notes with that tag. So what is different about how Roam does this? First, when you click on a tag in an app like Bear, you are taken out of the document you are working on to a list of files. This interrupts your workflow. Roam includes Linked References right in the document. (Because “Linked References” is a bit of a mouthful, I will just call them “backlinks” from now on.) Second, Bear tags work at the document level, but because Roam is an outliner, it can show you the exact paragraph that contained the relevant tag. (See the example image above where all the mentions of John Smith are highlighted from the notes about meetings in which he attended.) Third, the backlinks show up in the document as editable text, so you can work on them right there without having to open up the original document! Forth, you can filter and search your list of backlinks, quickly narrowing the list down to the most relevant results. And finally, tags in Roam are not just search terms, they are actually pages which you can edit.

To see how this all works, let’s go back to the John Smith example. If every time you have a meeting you add linked tags to everyone present, when you look at the backlinks at the bottom of John Smith’s page you can quickly filter the list by who else was present. For instance, you could narrow the list down to only those meetings where both John Smith and Jane Doe attended the same meeting.

And suppose at one of those meetings John Smith had been assigned a job, you would see the text “John Smith was assigned to write the annual report” right there in your backlinks, you wouldn’t need to go hunting for the initial notes about that meeting to remember what he had agreed to do. You could even edit the text itself to make a new page linked to “annual report” and then start making notes to send to John about what needs to be included in that report. Finally, since the “John Smith” tag is itself a page, you could include his contact information there so you’d have his email address handy when you are ready to send him those notes.

It may not be obvious from this example, but one of the advantages of such a system is that it can also reveal a lot of links you might not have consciously thought of when you were writing. If you still enjoy strolling around library stacks because you love how the Dewey Decimal System doesn’t just show you the book you are looking for but often helps you discover related books you didn’t even know you needed, Roam can off you’re a similar feeling for your own notes. The list of backlinks often reveal adjacent ideas and helps forge new connections in your own writing. There is even a “graph view” that turns these links into a pretty chart which you can explore within the app.

Backlinks might be Roam’s most notable feature, but it has many more tricks up its sleeve. (If anything, the developers seem to be going a bit overboard with all kinds of experimental features when some of the more basic functionality still need work!) I will focus on three of these features here. These are features tied to the core function of the app as a place to take notes. The app is also a database, and there are a lot of features which make use of that to programmatically output information based on queries, but I’ll skip those advanced features here. The features I think make Roam especially useful for taking notes are: transclusion, the sidebar, and Daily Notes:

Transclusion refers to the ability to embed a link from another note (or another part of the same note) directly into an outline. Let’s say I’m taking notes on fruit and have a section titled “apples” under which I list various types of oranges (Granny Smith, Gala, Fuji, etc.) and I include information for each, such as where to buy them, when they are in season, how they taste, etc. When I start another note with a recipe for apple pie, I might want to include my notes on Granny Smith apples in that note, rather than simply linking to the Granny Smith note (as in the John Smith example). Roam allows me to directly embed the relevant bullet points from my “apples” outline right in the document. And if I edit the Granny Smith information in one place, it will be updated everywhere else it appears! The following two pictures show how that might work. In the first picture we have the definition in context in the original note, and in the second picture we see it embedded in ta pie recipe.

The second feature is the sidebar: a sliding window pane that can appear on the right side of the screen. Any note (or section of a note) you are working on can be opened there for reference. I the picture below I have a shopping list note that I can update as I work on the recipe. The sidebar can handle multiple notes at the same time, and they can be collapsed or expanded as needed.

Finally, Daily Notes are a special kind of note that appear each day, with the date at the top. I was a little confused by this at first, but after playing with Roam for a week I found that I absolutely love using this feature. It encourages you to keep a running journal of your day. Rather than adding new notes for each topic you want to write about, you just tag them as you go. Remember, tagging something creates a new page that will automatically have a back-link that includes what you are writing in the daily journal! Because of the magic of backlinks, there is no need to create new documents for everything. That means you can just focus on writing and not worry too much about where things should go. I have found this tremendously liberating, and as a result I find I write a lot more notes than I used to.

In Roam the process of writing and the process of filing are entwined with each other, rather than two separate processes. I think this is what makes Roam such a joy to use, and so far no other app has managed to capture this feeling. Nor am I alone. I think this feeling is what explains the #roamcult hashtag. With other apps you often feel that each new piece of information added to the app makes it harder to find what you are looking for. My Evernote, for instance, often feels like an overstuffed shoebox whose lid no longer closes. But with Roam I feel that the more data I add to the app, the more useful all that data becomes. Maybe it just feels like a shiny new toy because I have only been using it for a few weeks? Only time will tell if this feeling is justified, but so far I think it really works.

As much as I like Roam, I think what I really want is something like Roam but better. I find the app already bloated with too many features, it lacks a good mobile app, and it can sometimes take a long time to load. Fortunately, a lot of other developers have been inspired by Roam to create similar apps, or add Roam-like functionality to existing apps. It is too early to tell if any of these will succeed, but one I am especially hopeful about is Obsidian because it comes from the same team behind Dynalist, and their vision emphasizes open standards and local control of your data. The Archive is another possibility. Inspired by the Zettelkasten Method of Niklas Luhmann, it actually predates the other apps, but I find Luhmann’s system a bit cumbersome to use compared to Roam and Obsidian. Thinktool is more of a traditional outliner, but it includes backlinks and transclusion like Roam. Other efforts can be found in this list of open-source Roam alternatives. And Athens is a more ambitious attempt to create an open source clone of Roam that matches all of its features. It is too early to tell which of these apps will succeed, but if any of them do it will be because of the inspiration provided by Roam.

- Also, there are some privacy concerns with regard to keeping sensitive information in Roam. (They say they are as safe as Evernote or Dropbox Paper, but how safe is that?) And it still lacks a dedicated mobile app, so while you can access it on iOS or Android, you will likely be frustrated by the experience. ↩

- If you do want a how-to here is a good guide to getting started. And, after you’ve mastered the basics, here is how to find out more. ↩

P. Kerim Friedman is a professor in the Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures at National Dong Hwa University in Taiwan. His research explores language revitalization efforts among indigenous Taiwanese, looking at the relationship between language ideology, indigeneity, and political economy. An ethnographic filmmaker, he co-produced the Jean Rouch award-winning documentary, ‘Please Don’t Beat Me, Sir!’ about a street theater troupe from one of India’s Denotified and Nomadic Tribes (DNTs).